Thursday, November 16th, 2017

Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light – Screening at Paris’ City Hall

Fifteen (15) years after Joanne and David Burke conceived of making a film about the African-American presence in Paris, they succeeded in producing Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light.

Joanne and David Burke

Joanne and David Burke

© Entrée to Black Paris

This award-winning, 1-hour documentary is touring the U.S. and has been shown at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Two nights ago, it was screened at the Hôtel de Ville de Paris, Paris’ City Hall, as part of the celebration of the centennial of the U.S.’ entry into World War I.

Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light focuses largely on the period between the arrival of African-American soldiers in France as part of the U.S. war effort to the Nazi occupation of France during World War II. It was screened before a mixed (race and nationality) audience and presented in French, thanks to a grant from the U.S. Embassy that funded the translation of the original script from English into French.

The film was preceded by a musical interlude provided by long time African-American expatriate Ursuline Kairson,

Ursuline Kairson and accompanist

Ursuline Kairson and accompanist

© Entrée to Black Paris

and followed by a panel discussion led by cultural producer Raina Lampkins-Fielder. Until recently, Lampkins-Fielder was the artistic director at the Mona Bismarck American Center in Paris.

Raina Lampkins-Fielder

Raina Lampkins-Fielder

© Entrée to Black Paris

The panelists for the evening were producer Joanne Burke, author Jake Lamar, associate producer and Black Paris tourism pioneer, Julia Browne.

Left to right: Jake Lamar, Joanne Burke, Julia Browne, and

Left to right: Jake Lamar, Joanne Burke, Julia Browne, and

Raina Lampkins-Fielder

© Entrée to Black Paris

Burke described how the film came to be, saying that she and her husband David believe that the United States’ biggest cultural contribution to the world is music and that they started their journey toward Paris Noir by researching everything they could about the influence that African-American music and musicians have had on Paris. They were introduced to Browne and the rest is history…

Lampkins-Fielder posed several questions to the panel prior to opening a Q&A session with the audience.

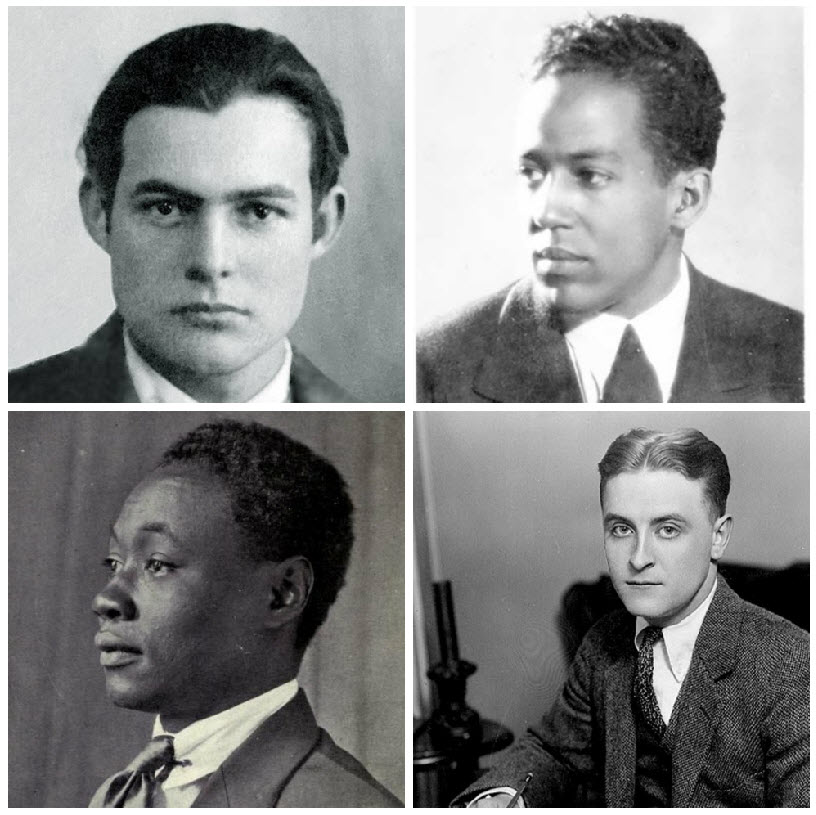

One of these questions pertained to the relationship (if any) that existed between African-American writers of the post-WWI era (examples include Langston Hughes and Claude McKay) and those of the Lost Generation (such as Ernest Hemingway and Francis Scott Fitzgerald).

Top, left to right: Ernest Hemingway, Langston Hughes

Top, left to right: Ernest Hemingway, Langston Hughes

Bottom, left to right: Claude McKay, F. Scott Fitzgerald

Collage by Entrée to Black Paris

Lamar and Browne responded by stating that there was very little interaction between these two groups. Browne emphasized her opinion that black and white American writers from the period were following parallel courses of development and Lamar stated that they had distinct reasons for coming to Paris in the first place.

A strong theme that emerged during the panel discussion was the difference between the “black & white” of race relations in the U.S. versus the nuanced relations that people experience in France.

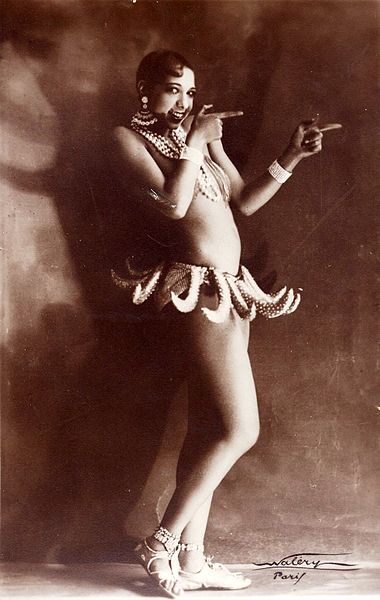

A final question from Estelle Lampkins-Fielder (daughter of Raina Lampkins-Fielder) in the audience about the exotic roles that Josephine Baker played on stage and screen prompted further discussion on this topic.

Estelle Lampkins-Fielder

Estelle Lampkins-Fielder

© Entrée to Black Paris

Browne remarked that because there were always political undertones in the shows and films in which Baker starred, she could not have portrayed an African American in these productions because she would be perceived as an American first and this would bring into focus the power play between France and the U.S.

Lamar stated that while Baker was starring in these exotic roles, African-American women in the U.S. could only hope to play the parts of slaves or maids and that the roles Baker played would be considered an advancement from an African-American perspective.

Josephine Baker in banana skirt

Josephine Baker in banana skirt

1927 - Image in public domain

Browne then added that while Baker was widely accepted in her roles, African women could not have played those parts in France during that era.

Lampkins-Fielder appealed to French people in the audience to express their feelings about the film and a couple of attendees shared that they see the deep influence of African-American culture in Parisian life today. Lamar concurred, indicating that he saw the tremendous influence of hip-hop and rap in Parisian culture when he moved here in 1993.

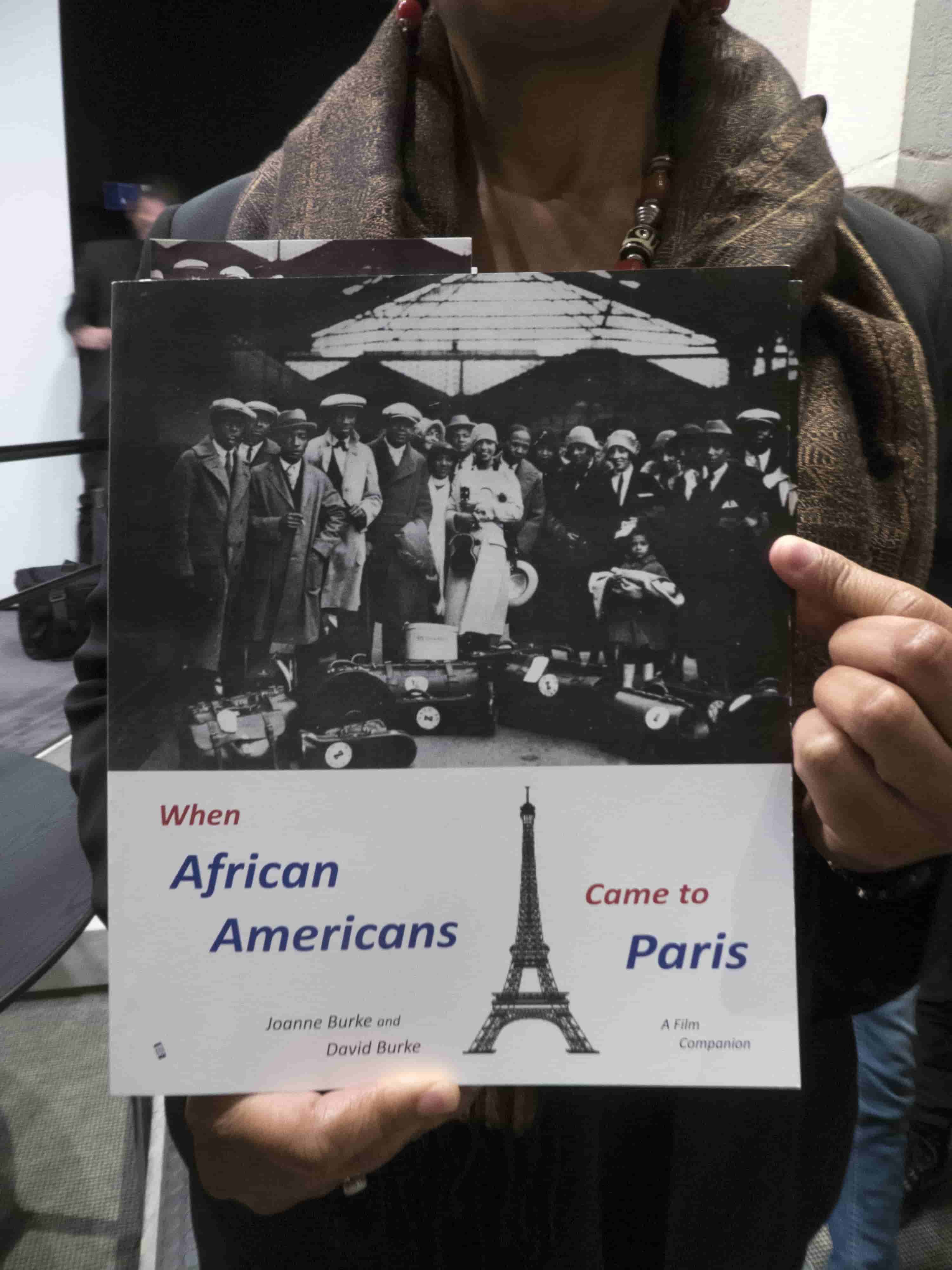

Burke ended the evening by informing the audience that she and David Burke have published a book entitled When African Americans Came to Paris as a companion to the film. Among its many features is Augmented Reality* content that delivers additional film footage, a list of recommended reading, and sources of archival material to compliment the film.

When African Americans Came to Paris - A Film Companion

When African Americans Came to Paris - A Film Companion

Book cover

© Entrée to Black Paris

*The Augmented Reality content for When African Americans Came to Paris is hosted on Blippar, the platform that hosts the AR content for the Beauford Delaney: Resonance of Form and Vibration of Color exhibition and catalog.

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!