Thursday, March 7th, 2019

Ouvrir la Voix - Speak Up

By Liz Adamo

Liz Adamo is the Wells International Foundation's 2019 Winter-Spring intern. As a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, she is researching a number of topics relevant to women of the African diaspora in Paris. In this article, she provides commentary on the 2017 French documentary, Ouvrir la Voix.

Ouvrir la voix is a film devoted to making a space for black francophone women’s voices to be heard. Translated into English as Speak Up, it is a documentary by Amandine Gay, a French woman of African heritage. It features a handful of women speaking about their experiences as black women in France and Belgium and fills an increasing need for women of the African diaspora these countries to claim their place and their voices in the 21st century.

Ouvrir la Voix

Ouvrir la Voix

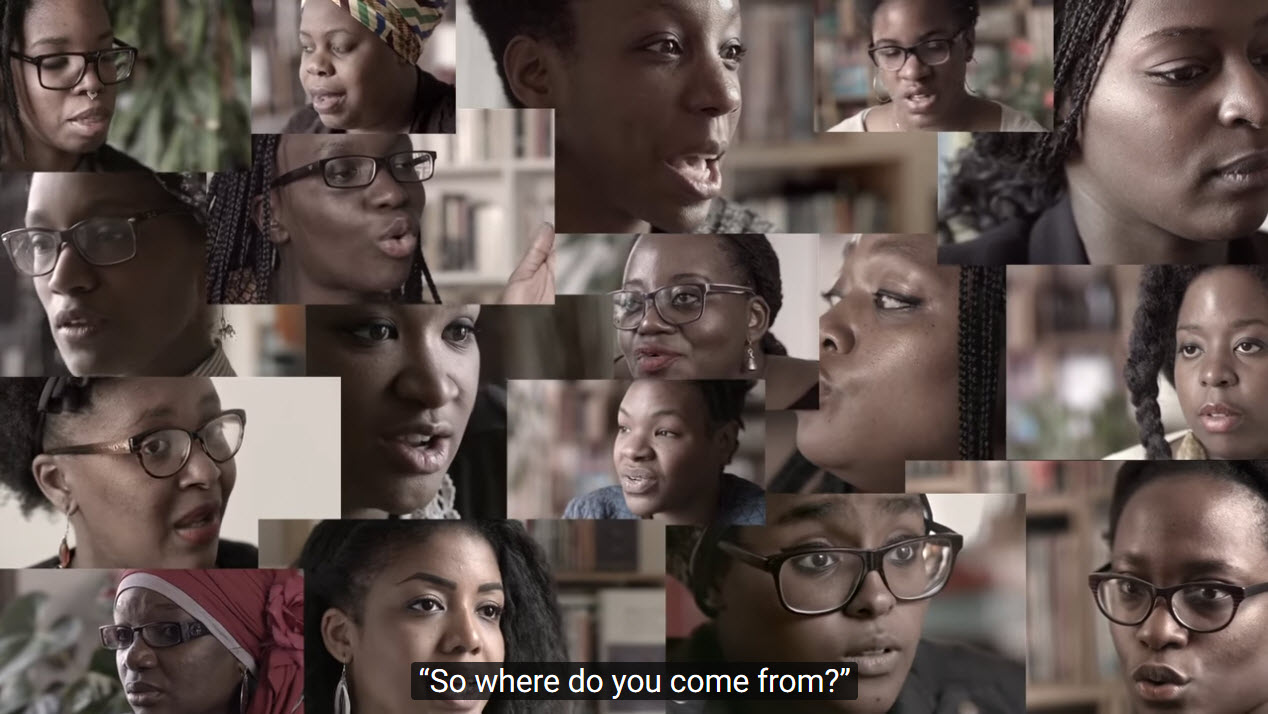

Screenshot from trailer

The film begins with the women’s descriptions of how they are depicted as “Other” in France and Belgium because of their blackness, as they are constantly having to answer the question, “Where are you from?” Black people have been present in France since the Revolution, and their numbers have grown steadily since the 1920s when African men (colonial subjects) who fought for France in WWI settled in the Hexagon after the war. This means that there are 3rd and 4th generation black people in France, and yet they are still subjected to the question of their origin because of their race. Given that most white people in France have at least one grandparent who immigrated but are not constantly asked the same question, this demonstrates the racial construction of citizenship in France as whiteness.

African-descended women are searching for spaces where they can be heard because, as women, they live at the intersection of racial and sexual politics in France. Their experience as women in France is markedly different from the experience of African-descended men in many ways, as the women in the film make clear. For example, they discuss at length the images of black women in French culture, dating back to colonialism, that depict them as either asexual caretakers or highly sexual Jezebels. These images affected the way that people viewed them as adolescent girls growing up in France. Religion also comes into play here, as one Muslim woman discusses how her concerns as a veiled woman are pushed aside by other feminists.

Only until recently have these issues been discussed in the public light. This is because in France, race (and gender) relations are dictated by a model called “universalism” dating back to the French Revolution. This view of citizenship promotes the concept that everyone is equal, and the same by law. People have the right to individual differences, such as religion or ethnicity, in private spaces but outward expressions of such differences are not readily accepted. In contrast to politics centered around gender, which have been acceptable since the 1970s Women’s Liberation Movement, discussions of (other) identity politics are difficult at best and many times hostilely received in France.

Several recent controversies about black women organizing in public demonstrate this contradiction. In 2017, a collective called MWASI organized an afro-feminist festival in which some meetings were reserved for black women only. The mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo (who is of Spanish descent) threatened to ban the festival for “excluding white people.” Because the festival took place in private venues, this was an empty threat. More recently, in 2018, the local government of the 20th district of Paris rescinded its funding for a “Feministival” because Rokhaya Diallo, a French woman of Senegalese descent, was invited to speak about afro-feminism.

Clearly, afro-feminism, the intersectional feminism of women of African-descent in Europe, is a hot-button topic in France today. This is because France claims to be “colorblind.” The accepted dogma in French politics is that speaking about race and identity politics reinforces and constructs differences, rather than alleviating them. However, many activists believe that France fails in many ways to address blatant racial inequality that exists today.

The reality is that citizenship in France is coded as whiteness. That is the reason these women, though born and raised there, must constantly defend their presence and assert their Frenchness. They are doubly or triply silenced in the French conception of citizenship by way of their gender and their race, and many times, as the film shows, by their religion or sexuality as well.

Amandine Gay

Amandine Gay

Screenshot from screening of Ouvrir la Voix at the Assemblée Nationale

However, black women are increasingly fighting this silence. Amandine Gay’s style in Ouvrir la voix is simple and powerful: nearly every shot in the film is an extreme close-up of her interviewee’s faces. We see them in every minute detail, and we are not distracted by anything in the background. We are absolutely focused on their voices. It is not difficult to understand, given the history of race, gender and citizenship in France, why Gay chose to frame her interviews this way.

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!