Thursday, November 13th, 2025

Our Visit to Bordeaux - Part 2

Cover image: Sculpture of Modeste Testas near the Bourse Maritime

© Entrée to Black Paris

While I always enjoy a good museum visit, I wholeheartedly prefer a well-conceived and informative walking tour when I visit a new city.

That is precisely what M. Karfa Diallo, founder and director of Mémoires et Partages, delivered to Tom and me during our recent visit to Bordeaux.

Monique Y. Wells and Karfa Diallo

Monique Y. Wells and Karfa Diallo

© Entrée to Black Paris

A nonprofit association, Mémoires et Partages offers three regular walks in Bordeaux and additional walks by special request—all in French.

Of the three regular walks, Tom and I experienced Coeur de Ville (literally, "Heart of the City") and Quartiers de Sucre ("The Sugar Quarters").

On the overcast morning of October 29, we met M. Diallo for the Coeur de Ville walk at 10 AM. We rendezvoused on the Parvis des Droits de l'Homme, a square that stretched in front of the Ecole de la Magistrature, two towers and a stone wall that are remnants of the Fort du Hâ fortress, and the Palais de Justice.

Diallo explained that each Mémoires et Partages tour features six themes that are associated with tangible heritage (the stops on the tour) and intangible heritage (stories that reflect each theme). The themes address every aspect of the Black experience of slavery and the slave trade, from capture to emancipation.

To provide background and context for our walks, Diallo first talked about the trans-African and Arab-Muslim slave trades that predated the trans-Atlantic trade.

Because certain African chieftains were already engaged in the trans-African and Arab-Muslim slave trades, it was not necessarily shocking that they would provide European traders with captives when the traders came to the continent.

Convoy of Captive African Women

Convoy of Captive African Women

Alphonse Lévy

19th century, Brown and gray ink wash

Reproduction on display at Musée d'Aquitaine

Image source: Slavery Images

License: CC-BY-NC 4.0

The trans-Atlantic slave trade differed from these preexisting practices because Europeans codified slavery based on race.

Diallo also pointed out that while the Arab-Muslim and trans-Atlantic trades resulted in the enslavement of a similar number of Africans (we do not have exact numbers for the Arab-Muslim trade), the trans-Atlantic trade operated within a significantly shorter time frame—a few centuries for the triangular trade compared to over a millennium for the Arab-Muslim trade.

Because it relied almost exclusively on the maritime transport of captives, the trans-Atlantic slave trade could move greater numbers of its human cargo more efficiently than the Arab-Muslim trade.

Prior to setting out on this first walk, Diallo told us that the medieval Fort du Hâ was used as a detention center for Blacks whose presence on French soil either had not been lawfully reported in compliance with the "Police des Noirs" (the "Blacks Policy" established under the reign of Louis XVI in 1777) or had exceeded the allotted lawful duration. They were held at the fort until arrangements were made to send them back to the French Antilles.

Fort du Hâ - Tour des Anglais

Fort du Hâ - Tour des Anglais

Guiguilacagouille

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

CC-BY-SA-3.0

Fort du Hâ - Tour des Minimes

Fort du Hâ - Tour des Minimes

Guiguilacagouille

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

CC-BY-SA-3.0

Following this introduction, we proceeded to the central area of the city. The center of Bordeaux is a pedestrian zone, so we were able to stroll and talk without the distraction of automobile traffic. The buildings there are pristine, thanks to the efforts of former mayor Alain Juppé to clean the façades that had been impregnated with pollution.

We ducked into the Cinema Utopia, formerly the Eglise Saint Siméon. There, we learned that in the early 19th century, the disaffected church was used as a maritime training school for disadvantaged youth. One can only imagine how many of them sailed on ships used for direct trade with the French colonies or the triangular trade.

In 2002, the largest room in the movie house was named after Toussaint Louverture, the principal general of the Haïtian revolution.

Karfa Diallo points to the Salle Toussaint Louverture

Karfa Diallo points to the Salle Toussaint Louverture

© Entrée to Black Paris

Farther along the route, near the colossal Place de la Bourse (formerly Place Royale), Diallo pointed out mascarons on the façade of a building. He talked about how some of these have African features and talked about the creolization of the population because of forced miscegenation.

Mascaron with African features

Mascaron with African features

Rue Fernand Phillipart

© Entrée to Black Paris

From Place de la Bourse, we made our way to Promenade Rue Sainte Catherine and followed it to Place de la Comédie. The Grand Théâtre, which serves as the city's opera house, dominates this square.

Diallo told us about the fresco by Jean-Baptiste-Claude Robin that has decorated the ceiling of the performance hall since 1777. Among the representations is an allegory of the City of Bordeaux—a woman at whose feet lie the riches of the city, which are portrayed as wine (grapes), ships, and enslaved Black people.

Detail of the fresco representing enslaved Black people as part of Bordeaux's wealth

Detail of the fresco representing enslaved Black people as part of Bordeaux's wealth

Jefunky

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

CC-BY-SA-4.0

Our walk ended at Place des Quinconces (the largest square in France), where a funfair occupied the entire space between the Girondin monument (a column and fountain) and two columns near the Gironde River.

The Girondins were a political faction during the French Revolution. Several of its members spoke out in favor of the abolition of slavery, including its leader, Jacques Pierre Brissot.

The next morning, we met M. Diallo at Place Pierre Renaudel in front of the Eglise Sainte-Croix (near the Gare Saint-Jean) to begin the Quartiers de Sucre walk. More than twenty sugar refineries were located in this area during the height of France's slave trade and Bordeaux's direct trade with the Caribbean colonies.

Under sunny skies, we walked up rue Camille Sauvageau and passed a modern residential building in which the remains of a sugar (sucre) refinery had been found during its construction. The discovery is evoked by a sign in the courtyard.

Le Patio des Fours à Sucre

© Entrée to Black Paris

At the Saint-Michel Basilica and bell tower, we learned about the "mummies of Saint-Michel" and the myth that one of them was a Black person.

Monique Y. Wells, Karfu Diallo, and Tom Reeves near Saint-Michel Basilica

Monique Y. Wells, Karfu Diallo, and Tom Reeves near Saint-Michel Basilica

Photo courtesy of Karfu Diallo

Near the Marché des Capucins, we walked down a street where several stores sell produce and other foodstuffs from Africa.

Occasionally, we came across street signs that gave a bit of history about the locale. Diallo explained that Mémoires et Partages actively advocates for the placement of clarifying signage on streets named after individuals who were involved in the trade or owned plantations in the Caribbean.

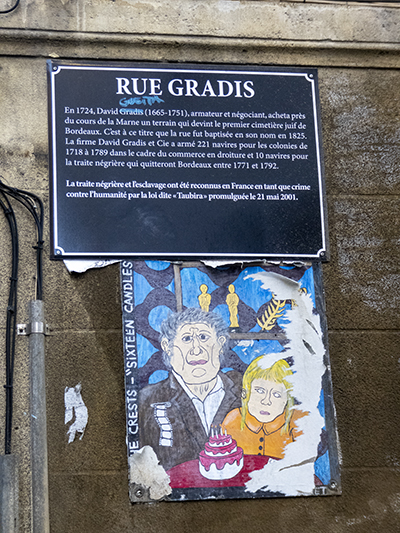

We saw one of these signs near Place de la Victoire. It informs passersby of the involvement of David Gradis (after whom the street is named) in slavery and the slave trade and categorically states that France has declared slavery and the slave trade crimes against humanity.

Discussing the street sign at rue Gradis

© Entrée to Black Paris

Rue Gradis street sign

© Entrée to Black Paris

We passed another example of a Creole mascaron on rue de Mirail.

Mascarons at rue de Mirail

Mascarons at rue de Mirail

(Creole mascaron at far right)

© Entrée to Black Paris

As we walked past an unmarked building that once housed a Carmelite monastery, Diallo told us about an 18th-century African man who, after securing his emancipation, joined Bordeaux's Carmelite religious community as a monk. He discovered how to transform wine into vinegar, and he sold his product in the streets and on the port of Bordeaux.

The vinegar is called "Tête Noire" ("Black Head"), and it is still sold today.

Label for Tête Noire Vinegar

Label for Tête Noire Vinegar

Image reproduced with permission

We finished the walk at the Musée d'Aquitaine, where we began our dive into Bordeaux's history of slavery and the slave trade the day before. (Read about it in Part 1 of this blog post HERE.)

That afternoon, we found our way to the Modeste Testas sculpture on the quai des Chartrons after having lunch in the Chartrons quarter.

Sculpture of Modeste Testas near the Bourse Maritime

Sculpture of Modeste Testas near the Bourse Maritime

© Entrée to Black Paris

We were intrigued when we realized that Woodly Caymitte (aka filipo), the artist who created the commemorative sculpture called Clarisse for La Rochelle in 2024, also created this work.

Artist's signature at base of Modeste Testas

Artist's signature at base of Modeste Testas

© Entrée to Black Paris

Modeste Testas (circa 1765-1870) was born Al Pouessi in Ethiopia. At the age of 14, she was captured in a raid and taken to West Africa, where she was purchased by Bordelais merchants named Pierre and François Testas. They took her to Bordeaux, where she was baptized Marthe Adélaïde Modeste Testas and subsequently taken to the Testas brothers' plantation in Saint-Domingue (present-day Haïti).

Modeste bore two children for François Testas before he took her and another enslaved person named Joseph Lespérance to the U.S. in 1795. Testas decreed that both would be freed upon his death, provided that they married.

The emancipated couple returned to Haïti, where they lived on land that Testas had bequeathed to Modeste. They raised a family there.

Modeste Lespérance died in 1870 at the presumed age of 105. One of her grandsons served as president of Haïti from 1888 to 1889.

For information about Mémoires et Partages' tour offerings, click HERE (Website in French).

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!

Our Walk: Black History in and around the Luxembourg Garden - Click here to book!